Disorders of Sexual Development (DSD) and Repeated Early Embryonic Loss (REEL)

There are a lot of reasons for a horse to be less fertile or infertile. Two groups of causes are the Disorders of Sexual Development (DSD) and the cases where a horse is fertile but it repeatedly loses the embryo in an early stage of gestation (Repeated Early Embryonic Loss or REEL).

Disorders of Sexual Development (DSD)

DSD’s are classified as a disorder in which the sex of an animal does not develop correctly. This can either be at the level of the external genitalia or internal at the level of the gonads, hormones or chromosomes. Some of these causes are hereditary, some of these are not. Horses with DSD’s can display an absent or abnormal oestrus, behaviour and/or body size not corresponding with their sex, unusual confirmation or characteristics of the genitalia (absence or for example smaller gonads) and reduced fertility or infertility.

Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (AIS)

Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (AIS) is a hereditary condition passed down through the X chromosome. It is caused by a mutation in the androgen receptor (AR) gene, which prevents androgens (male hormones) from working properly during embryo development. Therefore, the normal development of male traits in horses with male chromosomes (46XY) is disrupted. Depending on how sensitive the androgen receptors are to the hormone, the horse’s appearance can vary from female-like genitalia to male-like genitalia, but with issues with infertility. At CombiBreed two different mutations causing AIS in horses are tested, one which is known to occur in American Quarter Horses and related breeds (test code P506) and one which is known to occur in Warmblood horses (test code P309).

Chromosomal abnormalities

A horse normally has 31 pairs of autosomal chromosomes and 1 pair of sex chromosomes, resulting in a total of 64 chromosomes (euploid). A mare has two X chromosomes (XX) as sex chromosomes, while a stallion has one X and one Y chromosome (XY). If either during development of the egg cell or sperm cell an abnormal amount of sex chromosomes develop (for example two instead of one), an embryo with more or less sex chromosomes than normal can be formed, for example one or three instead of two. Another option is that cleavage of the embryonic cells develop differently than normal and a mosaicism appears; two different cell lines in one embryo with both a different set of sex chromosomes, for example part of the cells are XX whilst part of the cells are XXY.

Examples of chromosomal causes of DSD are:

- XO – only one sex chromosome is present, the X chromosome, this is also called Equine Turner Syndrome. Most mares with Turner Syndrome have underdeveloped reproductive organs and may exhibit other developmental abnormalities. The majority of affected animals are infertile. YO is never reported since this is not viable (embryonic lethal) and embryo’s die during early embryonic development.

- XXY – two X chromosomes and one Y chromosome, also known as Klinefelter Syndrome. Most animals with Klinefelter Syndrome have underdeveloped reproductive organs, and the condition may be associated with infertility.

- Mosaicism – if a proportion of the analysed cells display an abnormal number of (sex) chromosomes, this is referred to as mosaicism. Any combination of (most often two or three) cell lines with sex chromosomes like XX, XY, XO, XXY, XXXY, XXXXY can be present.

Repeated Early Embryonic Loss

In cases of REEL (Repeated Eary Embryonic Loss), fertilisation of the egg cell occurs and an embryo forms, but due to different reasons the embryo dies within the first 45 days of gestation. It is known that reciprocal translocations can be associated with Repeated Early Embryonic Loss (REEL).

In a reciprocal translocation, segments of two different chromosomes are exchanged. Reciprocal translocations may occur between a variety of chromosome pairs, although not all possible combinations have been investigated. In a Robertsonian translocation on the other side, an entire chromosome becomes attached to another chromosome. Translocations are often ‘de novo’, meaning that they are not inherited from the parents but happen ‘accidentally’. Not all embryo’s with a translocation will die, some are viable and will become healthy horses. Which ones are viable and which ones are not, depends on the genes affected by the translocation and how important these are in embryonal development and for normal body function. The surviving embryo’s will in general outgrow to healthy horses, but are often less or infertile. A mare with a translocation is usually unable, or only with great difficulty able, to produce healthy egg cells. Even if fertilisation does occur, the resulting embryo often fails to develop properly, leading to early embryonic loss. Similarly, stallions with chromosomal abnormalities generally produce few or no viable sperm cells, which typically results in failure to establish a pregnancy or in early loss of the embryo during gestation. Although chances are low, animals with chromosomal abnormalities (either translocations or sex chromosome abnormalities) producing healthy offspring are described in literature.

How are chromosomal abnormalities diagnosed?

Most chromosomal abnormalities can be diagnosed with karyotyping. Karyotyping is a valuable diagnostic tool, particularly in evaluating mares with reduced fertility or repeated early embryonic loss (REEL). By visualizing the complete set of chromosomes within a cell under a light microscope (making a ‘photograph’), this technique allows us to identify a variety of chromosomal abnormalities. The process involves isolating cells and arranging their chromosomes into a standardized karyogram for detailed analysis. These karyograms can reveal anomalies such as trisomies, deletions, insertions, and both reciprocal and Robertsonian translocations.

The equine karyotyping test can be performed on a sodium heparin blood sample. For optimal results, karyotyping should be performed on a 4 mL sample. To maintain sample integrity, it is recommended to send the samples as soon as possible after collection. If transportation exceeds one day, the samples should be stored at approximately 6°C.

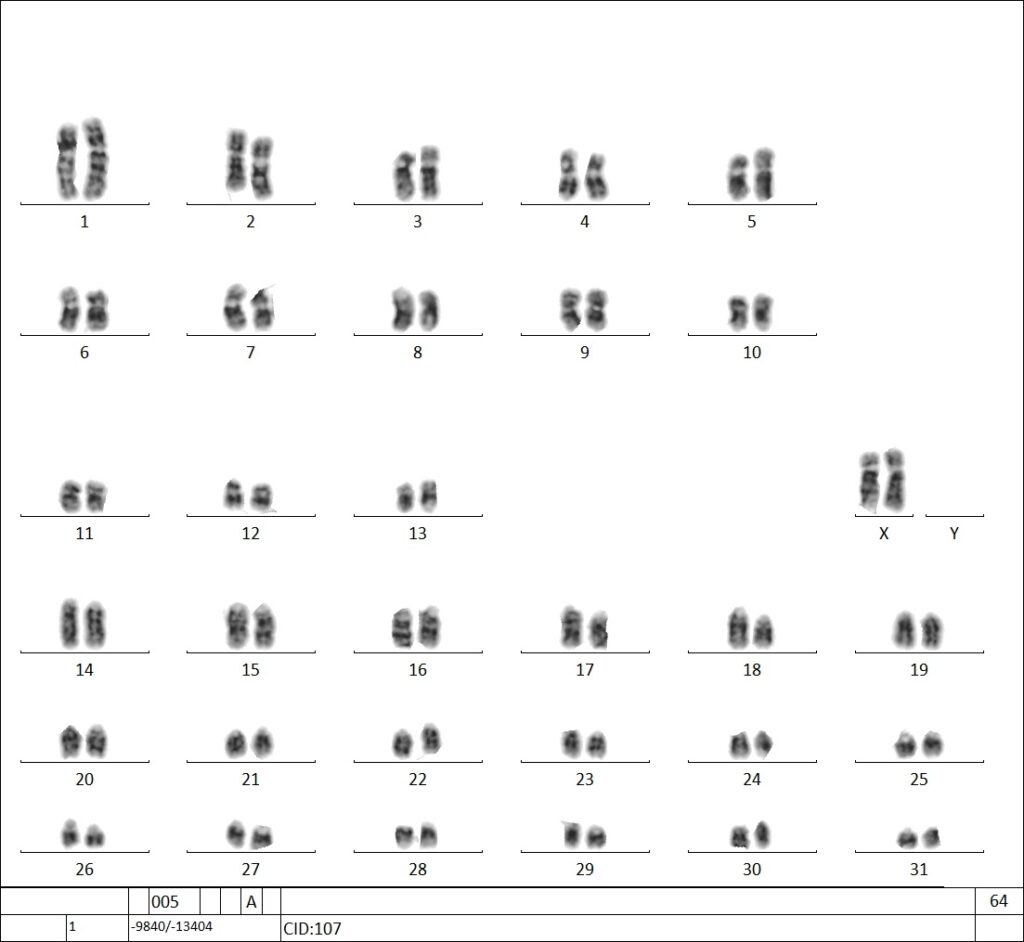

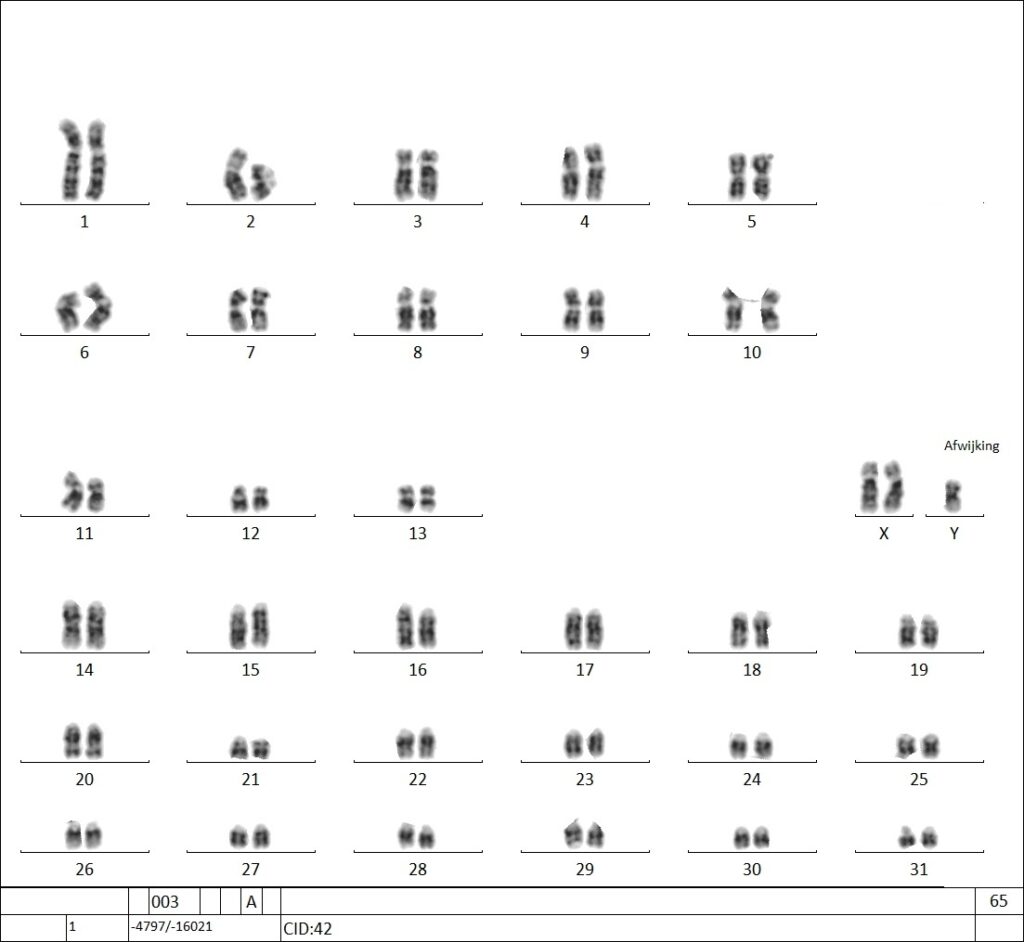

An example of a karyogram without abnormalities can be found in Figure 1, whilst an example of a karyogram with abnormalities (in this case Klinefelter Syndrome) can be found in Figure 2.

Figure 1: A euploid (normal) karyogram of a mare, showing the 64,XX karyotype.

Figure 2: In the karyogram, three sex chromosomes were identified – two X chromosomes and one Y chromosome (see ‘afwijking’). This condition is known as Klinefelter Syndrome.

Relevant tests

- P309

- P335

- P506

-

P335

P335Karyotyping – Horse

- All breeds

- Multiple systems